By: Nate Bek

What makes pre-seed investing so paradoxical?

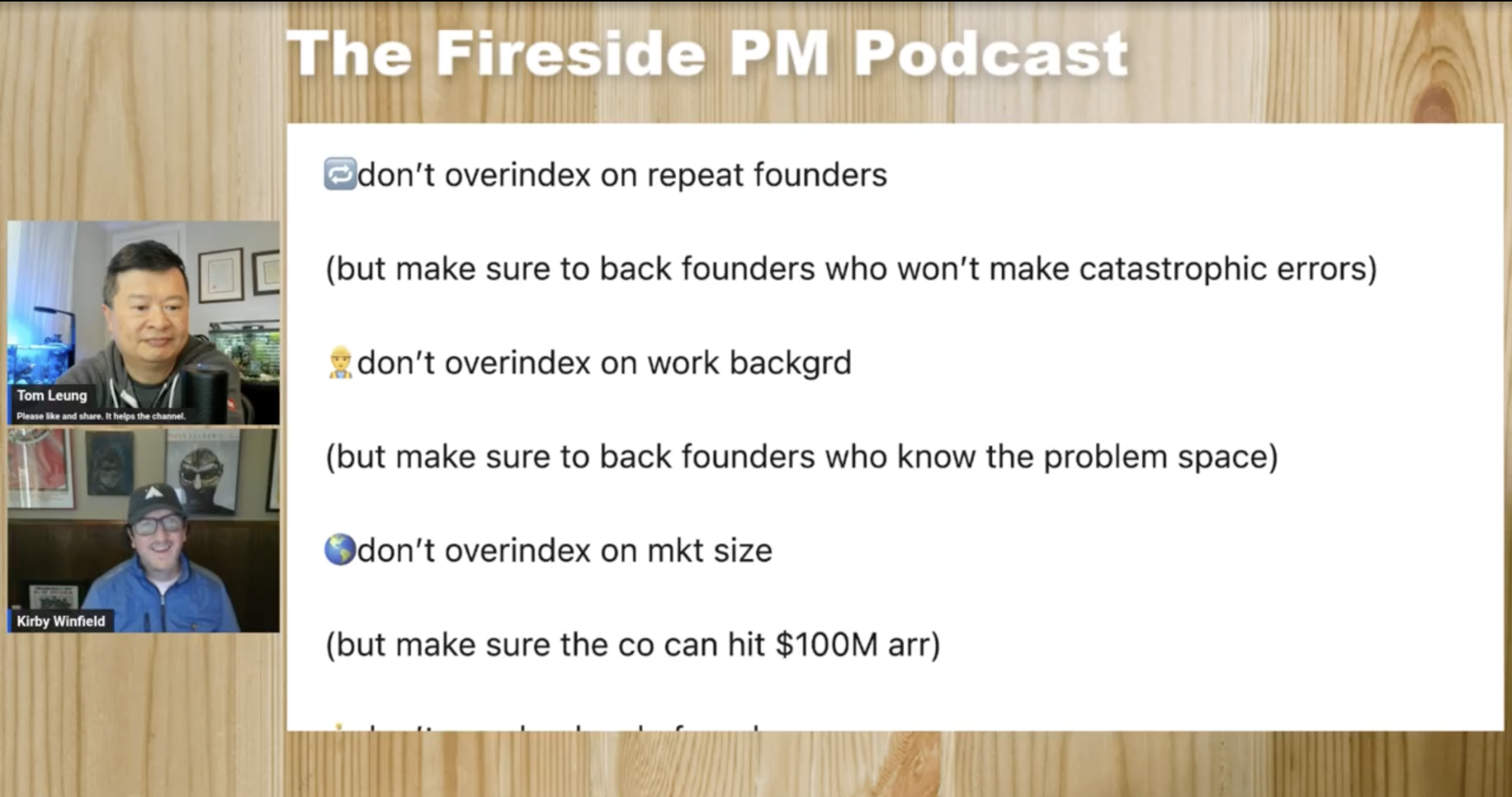

During a live Q&A session, Tom Leung, host of "The Fireside PM Podcast," posed this question to Kirby Winfield. Inspired by his LinkedIn post — which highlights several contradictions in pre-seed investing — Tom asked Kirby to methodically break down his insights, starting with, "Don’t over-index on pedigree," and, "Make sure to back PhDs."

“As an investor, I'm constantly trying to understand my mental algorithm,” Kirby says. "I started thinking, ‘I'll just use my gut. I'll know it when I see it.’ But then I unpacked my gut instincts and questioned what’s informing them… For every gut reaction you lean into, there's an equally valid instinct leaning the other way.”

Throughout the interview, Kirby untangles these paradoxes and shares his experiences, line by line.

Here are some key takeaways:

Gut instincts matter — Pre-seed investing is complex, but gut instincts play a crucial role. Kirby says, “You balance everything, try to figure it out, then realize, ‘Yeah, it's your gut.’” Refining these instincts helps in evaluating founders effectively.

Credentials aren’t everything — A Stanford PhD doesn’t guarantee success. Kirby emphasizes, “If credentials were the key, every Stanford PhD would walk out with $50 million from a VC.” Focus on a founder’s ability to find product-market fit, tell a compelling story, hire top talent, and execute their vision.

Upstream biases — Later-stage investors often rely on patterns and biases. Kirby says, “You have to be very thoughtful about how you navigate it.” Overcoming these biases requires backing founders who can create massive outcomes, regardless of their background.

Charisma vs. substance — Charisma helps in pitching but can mask deeper issues. Kirby says, “There’s a fine line between charisma and charlatanism.” Founders need more than just sales skills to succeed.

Revenue vs. customer love — Early success is about user love, not revenue. Kirby says, “It just matters how much the people using the product love the product.” Look for passionate customers.

Background vs. problem space — Founder-market fit is crucial. Direct problem experience is key, not just industry background.

Market size vs. ambition — Great founders can turn small markets into big opportunities. Kirby says, “The biggest misses I have are ones where I loved the founder but hated the market.” Focus on the founder’s ambition and vision.

Keep reading for the full Q&A transcript, edited for brevity and clarity.

Tom: We are back with the Fireside PM Podcast, and I have Kirby Winfield from the great city of Seattle.

Kirby: It’s a beautiful blue sky, spring day, 60 degrees. We’re coming around that time of year where we get the rewards of having suffered through 120 days straight without sun.

You do have an amazing income tax in Washington State...

Don’t tell the legislature. Life’s still good. We still welcome a lot of our brothers and sisters from California who find their way up to our haven.

It's a trade-off, for sure. And there is no other place that is quite as beautiful as Seattle on a nice day. It's magical. Well, for those who don't know you, Kirby, why don't you just give us a little bit of an introduction, and then we can get into the meat of the conversation about pre-seed investing?

I was born and raised in Seattle. I went back east for college and graduated in 1996. After college, I moved to Manhattan to pursue a career in advertising.

Three months later, a friend called and said, "Hey, I'm starting an internet company. Come back to Seattle." So I did. I was the sixth employee at GoToNet and eventually ran marketing. We drove a third of Google's traffic and became a top 10 internet destination. We went public, and I was a 24-year-old running marketing for a $4 billion company.

That was my introduction to startups. I made every mistake in the book, but it was a forgiving time. I worked for two great co-founders, and luckily, it went well. We exited in 2000 and started another company, Marchex, where I was on the founding team. We also took it public and did a $200 million secondary offering. We bought many domain names, and I ran that business, growing it from $5 million to $50 million in just over two years.

I always say, “I mistook my good fortune for talent.” Like many, I thought, "These guys are taking companies public. I can do that." I believed I could be a CEO. I took over a venture-backed startup that raised $18 million and quickly found out it was built on questionable traffic. We pivoted to an analytics big data play, laid off two-thirds of the staff, recapitalized the company, and spent six months on Sand Hill Road shopping the deal. Two VCs were interested, but the existing VC crammed down the other. That was my introduction to venture capital. We sold the company a year later with a great outcome.

I did one more startup as a founder, raising a couple million dollars for a travel app that we sold to Expedia. Twenty years, four companies, four exits. But the ones I ran lacked the exit value of those where I just bet on the right founders.

After that last exit, I decided to switch it up and bet on founders. I did angel investing off my own balance sheet because it was at the intersection of what I liked and was good at. Most of my operating career involved tasks I didn't enjoy or excel at. As an investor, I focused on what I loved: marketing, networking, connecting people, events, and exchanging ideas. I learned from founders and offered valuable insights, having made many mistakes and had some successes.

Angel investing didn’t feel like a job. Founders appreciated my feedback, and I helped with customer introductions, hiring, and raising capital. Our mutual friend Oren Etzioni invited me to help spin out an incubator program. Eventually, LPs showed interest in a fund. I raised my first fund in 2019 and a second in 2021.

I've recently started getting into angel investing, and I definitely hear you that it is so fun talking to founders. You get a little vicarious thrill, knowing that they're on the hunt. Hopefully, I enjoy sharing some war stories and saying, "Hey, look, I know where you’re coming from. This is what I did, and some lessons I learned the hard way."

It's valuable because it’s something you can do that higher-level investors can't empathize with or share useful experiences about, beyond investment or board management. They've seen the strategy, but for the zero-to-one journey, you don't want a growth investor. You want a founder. You want someone who's been there and done that.

Well, Kirby, you did a post on LinkedIn that caught my eye. I'm going to share it on the screen here, and it has a very catchy start, which is, "Hey, pre-seed investing is easy," and then you go through a bunch of learnings. I thought it might be fun for us to go through each one and hear a little bit of the story behind it and how you arrived at that insight. The first one is, "Don't over-index on pedigree, but make sure to back PhDs." Can you say more about that?

As an investor, I'm constantly trying to understand my mental algorithm. It's like observing my own thinking process. I want to know why I’m leaning towards or away from certain founders. I map this to the data from the 80 investments we've made so far.

I started thinking, "I'll just use my gut. I'll know it when I see it." But then I unpacked my gut instincts and questioned what's informing them. What biases do I have? If you're honest and intellectually candid, you realize that for every gut instinct you lean into, there's an equally valid instinct leaning the other way. It's confounding.

It's like the midwit peak meme: the simpleton says a thing, the midwit overcomplicates it, and the genius circles back to the simpleton’s point. That's been my journey. You balance everything, try to figure it out, then realize, “Yeah, it's your gut.” This process of unpacking helps refine your mental model for evaluating founders.

You don't want to back people just because they worked at certain companies, held specific jobs, or attended prestigious universities. Outcomes are distributed more broadly than that. If credentials were the key, every Stanford PhD would walk out with $50 million from a VC. But credentials don't make someone a founder. Can they hack their way to product-market fit? Can they tell a compelling story, hire top talent, raise funds, get press, and close deals? None of this is guaranteed by a PhD.

At the same time, my job is to help founders raise funds from big venture capital firms, which often back Stanford PhDs. It might feel safer to back someone with certain credentials because they match patterns seen from later-stage investors. But that's not the right approach for pre-seed investing.

Our portfolio includes dropouts from state universities and Stanford PhDs. I think the job of investing at this stage is to curate… Investing at this stage is like being a DJ at a party. You don’t just play old-school hip-hop; you create an experience that appeals to everyone. Investing in startups requires a broad surface area, beyond any one credential set or market slice.

Let me ask you a couple of follow-up questions on the pedigree front. I’ve actually heard people take that argument even further and say, “You definitely don’t want the Stanford people, and you definitely don’t want the Google or Facebook people, because they haven’t suffered, and they don’t know how to make something out of nothing.” And if you got a Stanford PhD, you’ve been on a pretty golden path. What’s your take on that? Do you actually ding people?

It depends on who’s holding the piece of paper. If you moved here from rural India at 12, fought through the public school system, made it to college, and then leveraged that into a PhD at a great school, that's very different from someone whose parents were PhDs in California, with one running a tech company. It's about evaluating the whole person.

Some people have been at AWS for eight years because they were challenged and stimulated by the software engineering work and needed to build a nest egg. Now they want to start a company. Others have worked in machine learning at AWS for eight years and should stay there. My job is to figure out the difference between these two people who look identical on paper.

How do you do that? If they do look identical on paper, how do you tell the ones that should stay versus the ones that should go for it?

If I could bottle that, I could sell it. If I knew I had it — I just don’t know. I’ve built a Google form to score founders on different axis, but it doesn’t really matter whether I use it or not. At the end of the day, you get a feel for the person and their reasons for what they’re doing, the urgency they feel, the vision they have to build something meaningful, and their understanding of the journey. You evaluate their ability to execute on those things. That’s what matters, and that’s what we try to figure out.

Another follow-up question: you mentioned that sometimes downstream investors like that pedigree, or they put a lot of money against Stanford PhDs. Have you seen a case where you back a less conventional founder who’s producing a really legit, great growing business, and they encounter more headwinds than they should have because of that lack of resume, or do the numbers eventually speak for themselves?

It’s not companies that get parabolic growth, or they start to look a certain way from the numbers, and they have the right logos, and they’re in the right market. Those companies get funded.

It’s more the companies that, if it were a female founder who’s been at Microsoft for 18 years and is non-technical, or a male PhD from Berkeley, both companies are doing okay. But to be venture-backable at Series A, you have to be really great.

Historically, that’s always been the case, and then it wasn’t for a little bit, but now it is again. What does great look like? It can be that you’ve got good traction, plus a credential that takes you over the line. If you’re good but don’t have the credential that takes you over the line, or don’t have a profile that historically gets backed a lot, then you don’t clear the line.

People will give you the benefit of the doubt more if there’s a reason to give you the benefit of the doubt. I get it. I have a freaking English major from Middlebury College; my pedigree academically isn’t going to give me the benefit of the doubt. If I’m looking at me, then there’s someone similar but with an additional set of interesting credentials that signify their intelligence and depth of knowledge and ability to focus and think critically that I don’t have… Well, I would probably invest more in that person, too. That’s data. I’m not going to say that you understand why it happens.

It sounds like if your company’s killing it, then you could not even have a college degree. It’s like, “Wow, that chart is clear. It’s parabolic. Let’s pour gas on this.” But in many cases, they are in that gray area, and that edge goes to patterns that investors are comfortable with or have seen success with in the past.

They’re comfortable, probably because they at least think they have data that shows they’ll feel good about that bet and will make their investors money. The only reason they’re doing this is to make their investors money. There’s no other reason they’re doing this. That’s what VCs do.

The challenge exists in trying to unpack how much of that is a methodology. How much of it is PhDs making us more money because we give PhDs more money? It may be that it’s correlation, not causation, and that would be the argument. Certainly, we believe that talent is distributed equally. Opportunity isn’t.

We’re not an impact fund, but we have folks from every kind of background as founders in our portfolio. We’re on that side of that discussion. Breaking the cycle of, we’ve done this and it works, so we should keep doing it, even if you don’t know how it would work if you didn’t do it.

There’s no real A/B test at the growth stage. This is why it comes down to LP pressure. If institutional LPs pressure GPs to make different decisions at the growth stage, then investors at my stage are freer to do what we want. I’ve talked to female VCs at seed and Series A who know the data and see it, so they’re making investments, and they’re like, “Well, I want to back women, but 2% of venture dollars go to women. Am I going to be the one to change that, or am I just going to back a bunch of women that don’t get back to Series B and C?” It’s insidious.

It’s not a lack of desire on the part of early-stage investors to change it. It’s a lack of incentive at the later stage to be open to it. This is not something I pound the table about, but I’m just sharing my personal views about it. It’s something most people will not talk about. My goal is to back founders, regardless of their background, who can create that parabolic company. I don’t care, even if later-stage people make decisions based on biases or bad data. I don’t think it matters because it would be irresponsible of me to invest this way if I did think it mattered.

I’m backing people because it’s 2024, and I’m backing people who can create massive outcomes no matter who they are.

If you believe that you’re being meritocratic and completely data-driven, but you worry that later-stage investors aren’t, that creates a disincentive for you to necessarily back the best founder because you have to consider that part of being a great founder is the ability to raise capital down the line.

You have to be very thoughtful about how you navigate it. This woman, who is a Valley investor I was mentioning, she’s a stage later than me but still early. That was her conundrum. I won’t go founder by founder, but we have founders in Fund II who are from underrepresented backgrounds in venture who have Stanford PhDs.

My approach is simple: I don’t care where you’re from, who you sleep with, or what you do in your spare time. If there's something spectacular about you that maps to the problem you're trying to solve, I want to back you. That's the way everyone should approach it. But I’m just one person.

“I think TAM (Total Addressable Market) is an excuse people use to avoid investing in founders they don’t like.”

Don’t over-index on charisma. What I heard from you earlier in our conversation was, “Hey, you want someone that can raise more than they maybe should and hire people that shouldn’t join them and convince customers to buy stuff that’s not quite ready.” It sounds like charisma is a really great thing to have. What do you mean by not over-indexing on it?

There’s a fine line between charisma and charlatanism. You don’t want to just back a really good salesperson. It’s very hard to invest in founders with sales backgrounds, at least for me, because they’re all really good at selling you, but there’s a lot about the job that has nothing to do with selling, and it’s the same for founders. You have to be thoughtful.

The corollary to that is Seattle investors, when they see a Valley founder pitching them, they just want to give them money because Valley founders are so much more polished than founders in other markets because they’ve had so many more swings. They’ve worked at so many different startups. The startup culture is in the water there. They probably have five advisors who have founded companies already. You see that as an investor who doesn’t always see it and think, “Oh my gosh, this is the best founder in the world.” Well, no. No more so than they would be up here. They’re just better at pitching.

You can’t just back people who can pitch, but it’s very hard to back people who can’t pitch, even if they’ve got other skills.

“Don’t over-index on revenue, but make sure to back founders who can get profitable.”

At the earliest stage, it doesn’t matter whether you have $10,000 in revenue or $100,000 in revenue. It just matters how much the people using the product love the product. How sad would they be if it went away?

I care much more about logos than revenue. Do you have five recognizable venture-backed startups as customers, and do they love what you’re giving them? That matters way more than revenue. To raise a seed round now, you need $500,000 in revenue. Two years ago, you needed a pre-seed and two co-founders.

I’d rather have a founder who has customers and who absolutely finds their offering indispensable versus the dollar amount. What about repeat founders? “Don’t over-index on them, but make sure to back ones who won’t make catastrophic errors.”

One reason I wasn't a great founder was my cynicism and reliance on a playbook. Repeat founders can fall into that trap. The advice often is to back really young founders who don’t know what they don’t know. They'll run through walls if pointed in the right direction and eventually find the goal.

A repeat founder might move slower and have more to lose. First-time founders, especially recent college graduates, don't. Their work rate is incredible. But first-time founders sometimes run off a cliff because they weren’t looking down. They might bring on the wrong investor, hire the wrong person, or face co-founder issues.

The point is you can choose either and encounter problems with both. We back both kinds of founders.

“Don’t over-index on work background, but make sure to back founders who know the problem space?”

Just because someone was a data scientist at GitHub doesn't mean they'll automatically build a successful developer tools modern data stack technology. Product managers often want to start a company because they handle many tasks, but that's not the ideal archetype. They often lack direct responsibility.

We constantly tell founders we want founder-market fit. We want you to have a unique insight that nobody else has. The only way to have that is if you’re coming from the space where the problem exists and have worked on it directly.

There’s data supporting both sides. Yes, a successful founder might have come from WhatsApp and started a billion-dollar app analytics company. That's founder-market fit. But they could have easily been a crappy founder for other reasons. The first question is, are they going to be good at founding and growing a company? Everything else helps you feel more comfortable backing them.

It’s interesting how your post talks about these common characteristics, and for each one, there are examples and counterexamples for the rule. Ultimately, you just have to make a call. It’s not going to fit one pattern.

It's infuriating, and nobody explained this to me when I started as a venture capital investor. People often talk about luck. Many smart, hard-working people are in this job, and some get lucky while others don’t. You have to put yourself in the way of luck. You do that by getting the best deal flow, picking the best deals, and winning the deals you pick. Those are the three things that matter in venture capital. But the picking part is the hardest because of these challenges.

Market size. Some markets might be too small. I was listening to Jason Calacanis live stream, and someone pitched a marketplace for collectibles for tabletop games. I was like, wow, I don’t know how big that market is. What’s your take on how big the TAM needs to be?

I think TAM (Total Addressable Market) is an excuse people use to avoid investing in founders they don’t like. TAM is code for ambition. Amazon’s initial TAM was people who wanted to buy duck decoys. Then it was books, which was a shrinking TAM. Remember Justin.TV?

Oh, yeah.

We ran ads on that and got in trouble for it because it was pretty wild west. The thing is, with a great founder, the thing doesn’t have to be the thing. The biggest misses I have are ones where I loved the founder but hated the market. If you love the founder, find a way to like the market.

If you love the founder and hate the market, have you ever convinced the founder to look at another market, or do you just go with it?

No, because you don’t want to back the founder who will change their mind based on your feedback. So you just go. There are still deals we won’t do, like biotech. We won’t even take the meeting. There’s a marketplace-adjacent deal I’m looking at now, and we don’t do marketplaces anymore. We did it for Fund I, won’t do it in Fund II, but I like the founder. There’s a difference between market size and markets you don’t like. I don’t think market size matters. I do think there are markets I’m allergic to. Travel. Ad tech. Not surprisingly, markets I’ve operated in.

TAM is usually about ambition. If you’re not telling me why it’s going to be monstrously big eventually, your ambition is to get a small slice of a small market. Unless you’re a dynamic founder, I’m not interested.

Why did you change your mind about marketplaces?

All the easy ones have been done. They’re slow. There’s always margin compression and a leaky bucket problem. Lots of reasons.

Don’t ever back solo founders, but make sure to back singular visionaries.

People will back solo founders. Some investors won’t back solo founders because they like to have two people making decisions. I believe I’ll make better decisions by myself. Some investors don’t like that and won’t invest.

Don’t work with assholes, but make sure to back disagreeable ones.

I love this one because I look at my portfolio and the founders I work with, and I like them all. Is that a problem? There are investors who back disagreeable founders because they understand them. It’s challenging. There are very successful funds with notoriously jerk GPs. They make money for their investors. I think about it when I meet someone disagreeable. You need to be disagreeable because nobody will believe you. There’s a mythology of the disagreeable founder. Enough founders break that rule to show that it’s not an indicator of future success. Life’s too short. If you don’t like that, don’t invest in my fund. Should I make this investment because I don’t like this person?

You’d have to engage with them for years.

Right. If they’re really an asshole, they’ll eventually kill me because I don’t like them. It’s all turtles all the way down.

How do you engage with founders, and tell us more about Ascend?

We focus on AI, but we believe it’s the evolution of technology and disruptive founders creating new companies. We’ll call it AI-native SaaS. This moment in time, every 10 years or so, incumbents get big, built on old technology and philosophies, bureaucracies. They can’t strip out their core. With generative AI, you can build a new type of company from the inside. Like the shift from steam-powered to electric-powered factories, steam-powered ones will be displaced. Generative AI companies built from the inside out with Gen AI processes are more efficient. Companies built on old sectors won’t stay around forever. We believe you’ll create a new Salesforce, edtech company, Gusto, Bloomberg. That’s our thesis. We back incredible founders passionate about the future and how they’ll shape their industry. We do that primarily in Seattle.

At what stage should founders reach out to you? How far along should they be?

I had a founder ask this yesterday. It depends on the founder. If you’re a conventionally backable founder with a ton of credibility, it’s never too early. You can’t screw that up. If you’re like I was, pretty good but not beating down doors, you want your story straight, bootstrap for a while, and remove objections. It’s not fair, but that’s how it is.

For me, talk to me whenever you want. I want to be there as early as possible. We’re the first check into these companies. Come to me at the idea stage. We’ve done that time and again, from idea stage through Series B. We’re on the napkin, figuring out your raise with you, and even if you’re ready to partner, we’re there to say, "This go-to-market maybe doesn’t make sense," or "Have you thought about this product direction?" We don’t do it all the time, but with the right founder, we’re happy to do it. As a friend of founders, I say, be thoughtful about when you do that, depending on your marketability.